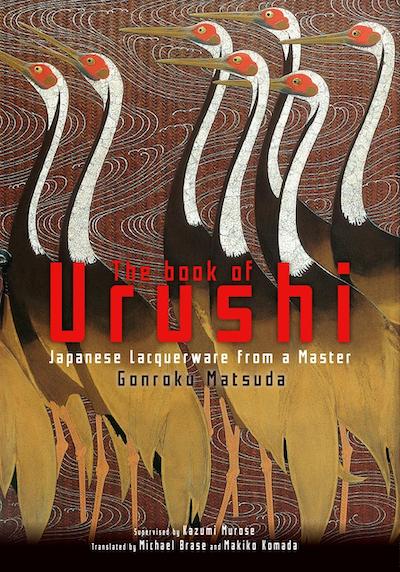

In my previous post (click here) I highly recommended Urushi no hanashi as a great book on the Japanese art of urushi (lacquer), while also mentioning my involvement in its English translation called The Book of Urushi. In this post, I’d like to thoroughly recommend The Book of Urushi and relate some “behind the scenes” problems of the translation project.

The translation was more than half finished when I was asked to participate together with Julia Hutt, my dear “work buddy” and then curator at the Victoria & Albert Museum. I was happy to be involved since the original Japanese book is one of my favorites, but I was also a little worried. As mentioned in the previous post, I thought this book was too difficult to translate!

One of the main problems in the translation was the use of many specialist terms in Japanese lacquer, describing various processes and techniques. For example, the word “togidashi” in togidashi maki-e refers to the process of sprinkling gold powder onto a design drawn in lacquer, consolidating the area with lacquer, and then coating the entire surface with lacquer. When hardened, the surface is abraded with a special charcoal until the design reappears. How could we express such a process in a few words in English?

Julia and I first translated the word “togu” as “grind.” However, Murose Kazumi-sensei (note: “sensei” is a Japanese honorific often used for master and teacher), the supervisor of this book and a Living National Treasure in the maki-e technique, was not happy with it. For him as a lacquer artist, “grind” sounds too rough or coarse, while the act of “togu” is more delicate and the surface of the related tools and materials are smoother than for grinding something with a whetstone, for example.

The word “polish” seemed much closer than “grind” to convey the meaning of “togu.” However, “polish” conveys the connotation of bringing out the luster, which would be more appropriate in referring to the polishing process used at the end of a production process. After a lot of discussion between Julia, Murose-sensei, and myself, we all decided that “abrade” would be the most appropriate English term.

The above was one of the many words and phrases that required much discussion during the course of translation. Actually I would often realize that I had misunderstood some parts that we had already translated, and then we would ask Murose-sensei and his former assistant, Nagata Tomoyo (whom I’ll mention later), for advice, and would correct those parts. We had to go back and forth, discussing and making amendments here and there. It was a demanding process, and seemed almost endless.

It got me wondering why all this had happened, since I had read it more than a few times and thought I understood it. Any text regarding Japanese lacquer art is like a surume (dried squid) or chewing gum: the more you chew (or read), the more the flavor (or meaning) becomes clear! I think the profundity of Japanese lacquer art is reflected in its vocabulary.

The English version of this book would not have been completed without the efforts of all those involved. First and foremost was Murose-sensei. As a lacquer artist himself and a pupil of Matsuda-sensei, he had such a profound understanding of the original text that he always answered our questions with clarity. Thanks are also due to Nagata Tomoyo. She is a researcher in the field of Japanese lacquer and a curator at the Nezu Museum, in whom Murose-sensei has enormous trust. They were always ready to help and provide us with valuable information. This work would not have been possible without them!

In addition, Michael Brase, who translated most of the book, was such an excellent and experienced translator that the Donald Keene Center for Japanese Studies at Columbia University awarded him an important prize for the translation of another book. He and his assistant, Suzuki Shigeyoshi, were a perfect team. Last but not least was Julia. Without her expertise in Japanese lacquer art and text-editing skills, I would not have been able to accomplish my task as translator! Moreover, she supervised the English translation of the entire book as an expert in the subject, adding to the reliability of the English version.

It is rare to find an English translation of a book on Japanese crafts which has been produced by such distinguished experts. It is truly a pleasure that this marvelous and important book on Japanese lacquerware has been made available to the world in good-quality English.

If you are interested, please click on the links below to find the book on Amazon and other stores.

Amazon.co.jp (possibly also available at Amazon.com).

Komada Makiko

Thank you for reading this far!

This post contains affiliate links. Koryuen participates in the Amazon Affiliates Programs. If you purchased a product through an affiliate link, Koryuen will receive a small commission, while your cost will be the same. Thank you for your understanding and cooperation!